“This is not an exhibition,” reads a sticker pasted on the beautiful art deco facade of Brussels’ Centre for Fine Arts, also known as Bozar. It’s a reference to “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”), the famous line of text in Belgian artist René Magritte’s iconic 1929 painting, which, of course, features a realistic depiction of a pipe.

Magritte is undoubtedly the poster boy of Belgian surrealism – after all, an entire museum is dedicated to his oeuvre just a few minutes up the road from Bozar. However, this comprehensive show at the Centre for Fine Arts, staged for surrealism’s 100th anniversary, reveals the multifariousness and vastness of the international literary, philosophical and artistic movement, while zooming in on its Belgian particularities.

Surrealism is an attitude of mind.

With its playful interrogation of visual representation and witty text, Magritte’s famed pipe painting – the actual title of which is The Treachery of Images – is characteristic of the surrealist ethos, which values the irrational and freely challenges imposed norms. In Belgium in particular, surrealists have long relied on humour as a subversive strategy. That’s reflected in the show’s title, Histoire de ne pas rire, which roughly translates as ‘a story without laughing.’ The phrase is taken from the book of the same name by Belgian poet Paul Nougé, who was the brain behind the Brussels surrealists and whose writings weave a common thread through the exhibition.

The beginnings of Nougé’s efforts can be traced back to 1924, the year French writer André Breton published the Manifesto of Surrealism – an event that marked the official birth of the avant-garde movement. The fact that a text, and not a specific work of art, laid the foundations is revealing. Surrealism is much more than an aesthetic approach, a style or a visual genre. At its core, the movement is about ideas, concepts and theories.

.jpg) Paul Nougé, The Juggler,1929-1930, Collection Archives & Museum of Literature (AML), Brussels. © Rights reserved

Paul Nougé, The Juggler,1929-1930, Collection Archives & Museum of Literature (AML), Brussels. © Rights reserved

Xavier Canonne, the Bozar show’s curator, writes that members of the surrealist movement “sought a transformation of the world through language and representation, a transformation that was inseparable from their political commitment to the Communist party.”

Accordingly, the exhibition, which brings together more than 360 objects from over 50 museums and private collections, not only features paintings, collages, drawings and photographic works by the movement’s main representatives – but also magazines, manifestos, card games, scribblings and personal items.

Language plays a crucial role, permeating not only surrealist artworks but also the show’s scenography, with significant quotes and poems gracing the museum’s walls. Many surrealists were primarily writers or poets, especially in Belgium. It was Nougé who drafted the titles of Magritte’s paintings for many years.

Many of the exhibited artworks are text based or use language as a central element – including Joan Miró’s painting poems, which partially inspired Magritte to produce his first word paintings in 1927.

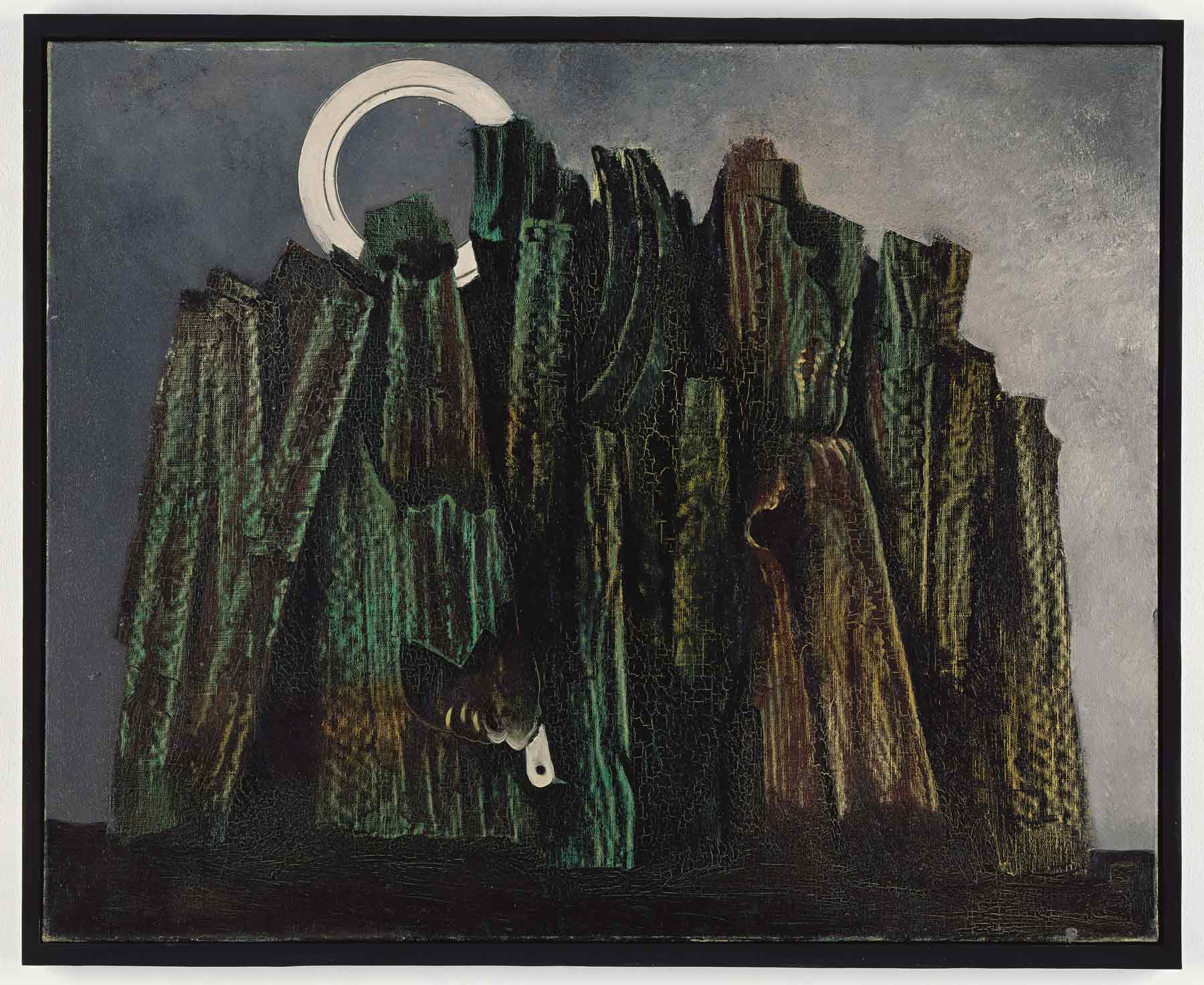

Max Ernst, Dark Forest and Bird, 1927, The Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch Collection, Berlin © Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Max Ernst, Dark Forest and Bird, 1927, The Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch Collection, Berlin © Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

While Magritte and Nougé are the main protagonists, the show gives room to a myriad of artists – from Max Ernst, Man Ray and Salvador Dalí to Paul Delvaux, Raoul Ubac and Max Servais – illuminating the similarities, differences and interconnectedness of the French and Belgian surrealist camps. Exchanges were plenty, but the Belgian surrealists were more discrete and conventional, and less didactic and flamboyant than their Parisian counterparts. The Belgians were also less interested in automatic writing methods and the role of the unconscious.

Meanwhile, the exhibition shines a much-needed light on the women artists active in the movement, such as Belgian painters Jane Graverol and Rachel Baes, whose significant contributions have long been overlooked.

Histoire de ne pas rire also looks beyond the focal points of Paris and Brussels, highlighting a local surrealist group in the unexpected Belgian coal mining town of La Louvière. Founded in 1934 by Achille Chavée, André Lorent, Marcel Parfondry and Albert Ludé, under the name “Rupture,” the group put on exhibitions with clear political aspirations. Indeed, it had the goal of “forging revolutionary consciences” and “contributing to the development of proletarian morality.”

The political climate of the era is present throughout the entire exhibition, putting the story of surrealism in a wider global historical context. Timelines on the walls highlight concurrent events, including anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe, the Shanghai massacre (a violent suppression of the Chinese Communist Party in 1927) and Charles Lindbergh’s first flight.

The Second World War proved to be disruptive for the movement. Belgian painter Delvaux refused to show his works, and Magritte took refuge by experimenting with impressionism, creating strangely sunny works in what is known as his “sunlit surrealist” or “Renoir” period.

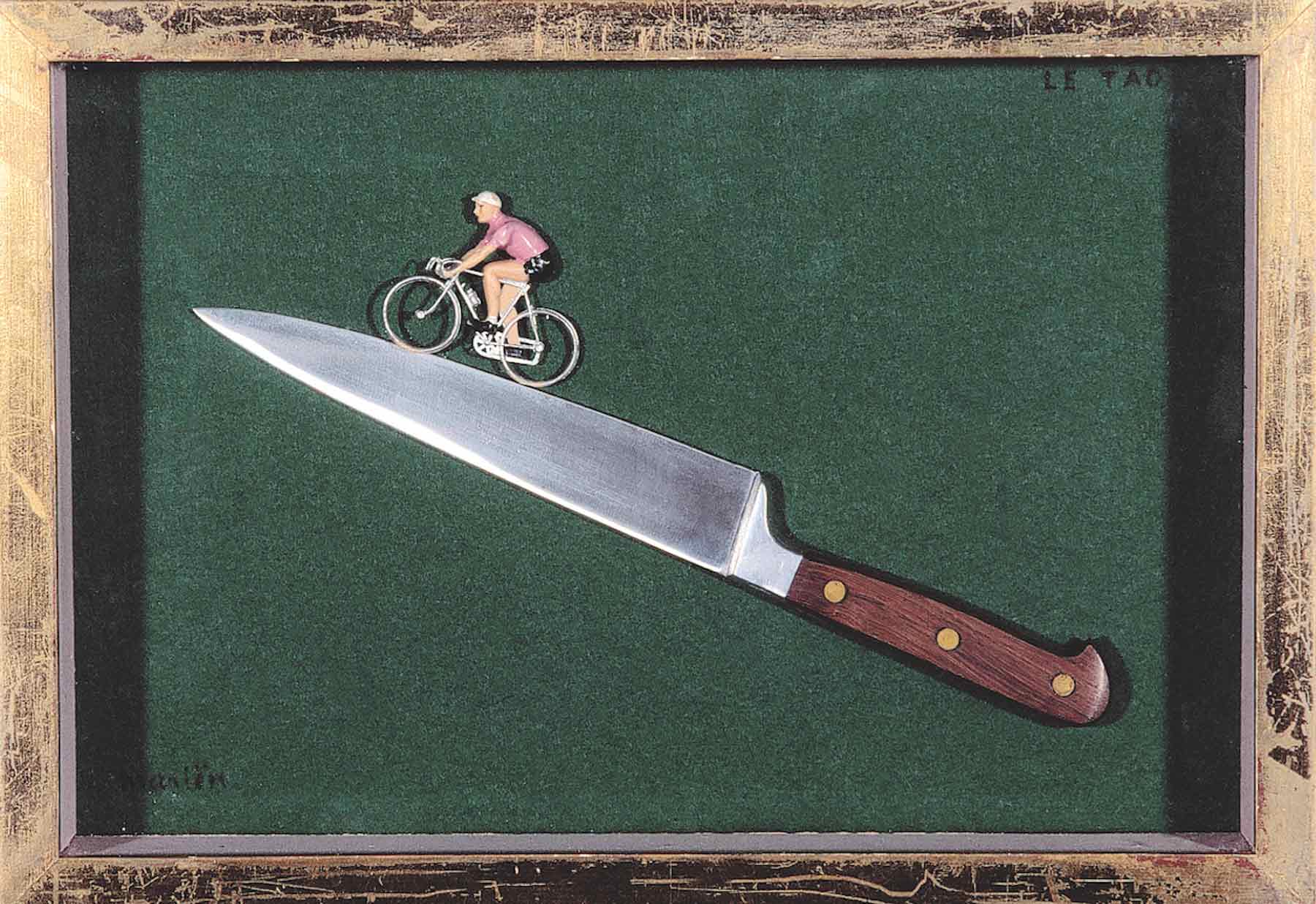

Marcel Mariën, The Tao, 1976, assemblage, Charleroi, The Hainaut Province Collection - Deposit at BPS22. © Fondation Marcel Mariën –L’activité surréaliste en Belgique

Marcel Mariën, The Tao, 1976, assemblage, Charleroi, The Hainaut Province Collection - Deposit at BPS22. © Fondation Marcel Mariën –L’activité surréaliste en Belgique

In France, surrealism was officially declared dead in 1969, when the Paris group formally disbanded. In Belgium, however, its story continued over the course of several generations, and its subversive humour has become deeply ingrained in the national psyche. Absurd situations such as the country being without a government for almost two years from December 2018 to October 2020 are often followed by a shrug and a declaration of: ‘Ah well, Belgian surrealism.’ To paraphrase Nougé, surrealism is an attitude of mind.

Bozar’s new exhibition is a brainy, thought-provoking show that tickles the mind – and might appeal more to viewers who appreciate poetic wordplay than those looking for pure visual stimulation.

At the exit, visitors are seen off with a last wall of text by Nougé: “Everything remains based on defiance and revolt. The status quo is, and will always be, humanly unacceptable.”

There is, without a doubt, a lot to think about. We’d recommend a coffee at La Fleur en Papier Doré on Rue des Alexiens 55, 10 minutes’ walk from Bozar – the Brussels café where Magritte and his contemporaries would do exactly that.

Histoire de ne pas rire is at the Centre for Fine Arts until 16 June .

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.