As AI advances, digital twins of everything from cities to aircraft to the human body are helping to predict real-world problems and optimise solutions. Now, the EU is working on cloning something even bigger: the Earth itself.

The European Commission’s Destination Earth project (DestinE) went live on 10 June this year, creating two digital twins – one focused on weather-induced extremes and the other on climate change adaptation.

“It’s not that often that one gets a sneak peek into the future,” Commissioner Margrethe Vestager said at the launch event.

A digital twin is a virtual replica of an object, used to simulate a range of potential situations and outcomes. These simulations are powered by data and machine learning models, leading to ongoing debate around their reliability and suitability for decision-making.

Improved computing and AI have made digital twins increasingly common across a range of sectors. But DestinE aims to surpass the capabilities of other digital twins. The Commission plans to add new twins by 2027, and by 2030 to combine them into a complete simulation of Earth’s climate.

“The aim is to provide science-based information at the highest possible level of detail, from a global to local scale,” Irina Sandu, project director at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), told The Parliament.

Potential applications include optimising the placement of renewable energy facilities and modelling the impact of climate policies.

This all comes at a cost. The project relies on Europe’s limited high-performance computing resources and demands huge quantities of data. The question is whether it can justify this cost by delivering new long-term insights on climate change, or whether it’s just a very expensive toy for the EU to show to the world.

Use cases

The DestinE system integrates data from the project’s partners, the Copernicus monitoring system, and more generic sources like the Internet of Things. The goal is to feed machine learning models with comprehensive data, recreating past conditions to predict future events.

DestinE’s short-term forecasting is recognised as reliable, and can already help Europe prepare for extreme weather events.

“If you can predict extreme weather, like hurricanes, a matter of a few hours or days in advance, that's already a good advantage to take precautions,” Florian Cortez, a researcher at the Egmont Institute in Brussels and the European Policy Centre, told The Parliament.

But that’s no guarantee of broader utility, because the "more long-term predictions become, the more uncertainty exists,” he said.

For that reason, its usefulness might be limited when it comes to making big decisions on climate policy.

“It makes sense to have digital twins as part of the toolbox for handling and enhancing preparedness against climate change,” Cortez added. “But it doesn't replace democratic processes to take decisions nor other sources of information, expert analysis or scientific efforts.”

Nevertheless, the model is likely to become more useful over time as it receives more data, and climate scientists refine its outputs.

“One simulation doesn't answer everything,” Sandu said. “So now we are going to use AI to see how we can build more trust, how can we make these models more reliable and give more information on how likely a scenario is going to be.”

Competition or collaboration?

The EU is not alone in its attempt to create a digital twin of the Earth, but DestinE is the most advanced and comprehensive model currently operating.

In March this year, American tech company Nvidia released Earth-2, an open platform simulation. It is used by The Weather Company in the US and the Central Weather Administration of Taiwan, where it helps forecast the precise locations of typhoon landfalls. Unlike DestinE, Earth-2 requires organisations to plug in their own data.

Elsewhere, NASA’s Earth Science and Technology Office is working on its own model with its Integrated Digital Earth Analysis System (IDEAS). Feeding in data from its network of satellites and elsewhere, NASA intends to use the model to track air quality, monitor wildfires, provide alerts and flood-risk maps, and predict coastal sea levels.

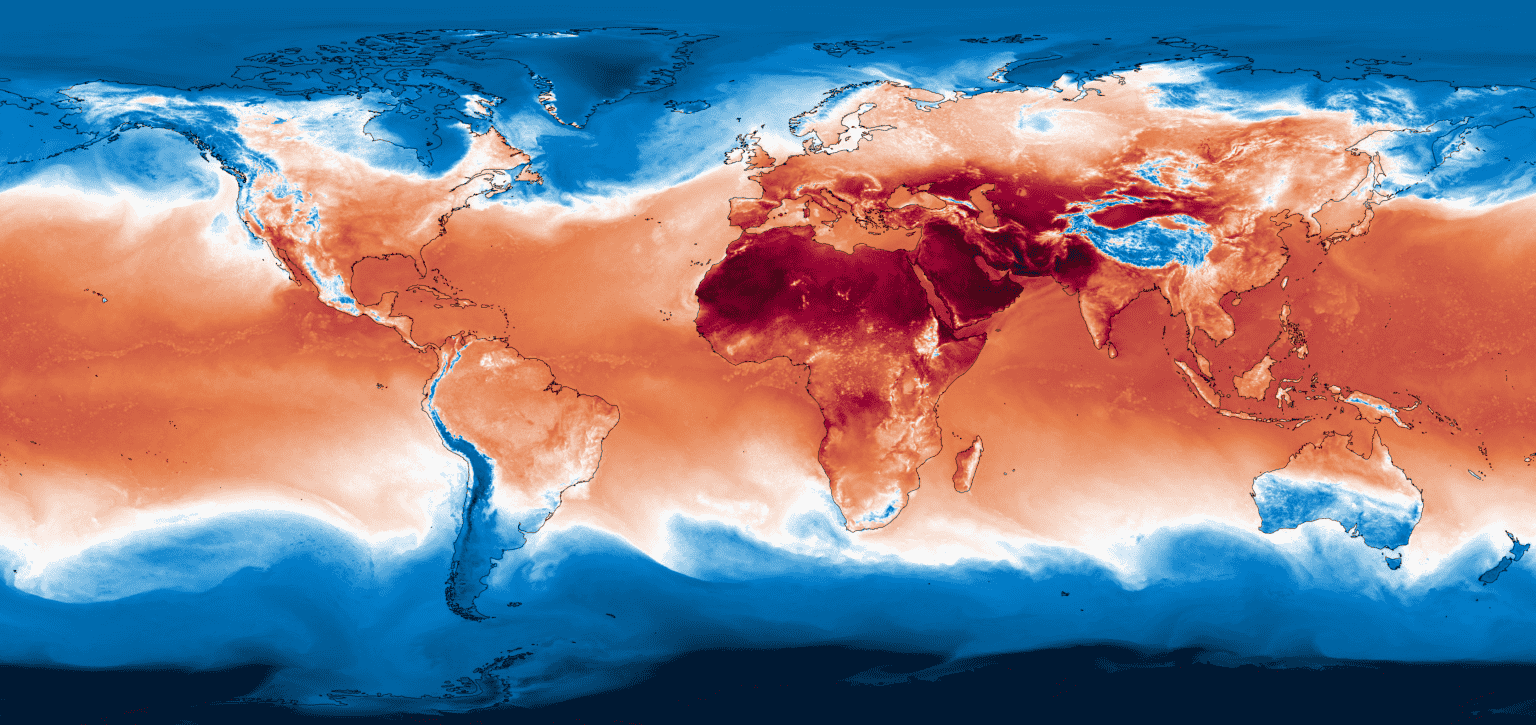

A snapshot of the surface temperature from one of the prototype projections of the Climate DT with ICON (at 5km resolution across atmosphere, land, ocean and sea-ice), performed on the EuroHPC LUMI supercomputer.

A snapshot of the surface temperature from one of the prototype projections of the Climate DT with ICON (at 5km resolution across atmosphere, land, ocean and sea-ice), performed on the EuroHPC LUMI supercomputer.

“Other projects are not as comprehensive and multi-year as Destination Earth, as it is set up to run for the next many years,” Cortez said. “There is potential for the EU to play a leading role in terms of digital twins of the Earth.”

In the longer term, Cortez sees a collaboration between DestinE and other models around the world, amplifying their capabilities. Work on the next two-year phase of DestinE began in June, immediately after its launch, which will update the system and ramp up its operations.

For now, the EU's digital twin is a good example AI's ethical use, Sandu added, to serve the public good and take a leading role in global climate policy. With extreme weather events becoming more frequent across Europe, its forecasting capabilities may prove essential.

“The investment makes sense given the enormous problem that exists in adapting to climate change,” Cortez said.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.