Europe’s ferry industry has a sustainability problem. While the sector makes a significant contribution to the European Union’s economy, generating upwards of €9bn a year, it has also become a growing source of greenhouse gas emissions. One solution? Electric ferries.

In 2021, maritime transport (ferries and cargo ships) represented up to four per cent of the EU total CO2 emissions, according to the European Commission. Over long journeys, greenhouse gas emissions rival those from flights, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Without immediate action, the share of emissions coming from transport could rise to 40 per cent by 2030. Electrification, which is already in use for cars, buses and trains, could help the ferry industry bring down its annual emissions by as much as 800,000 tonnes.

Beyond reducing emissions, the electrification of ferries comes with the added benefits of reducing noise and air pollution. Residents of Europe’s major port cities such as Hamburg, Rotterdam, Antwerp and Piraeus are surrounded by polluted air from the visiting fossil fuel-burning ships.

By electrifying maritime transport, “we can target climate change while also tackling the problem of pollution”, Germany’s Greens/EFA MEP Jutta Paulus tells The Parliament. “I think there will be a push from the public to go towards electric ferries and away from fossil fuels in their cities.”

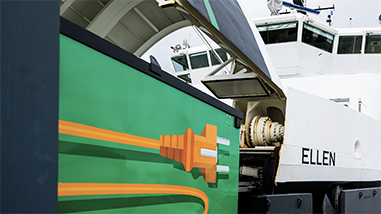

Electrifying ferries would require building a new fleet of green vessels to replace existing, gasoline-guzzling, CO2-emitting ships. That’s where Ellen, the world’s longest range all-electric ferry, comes in.

The Ellen ferry was built in 2019 as part of a four-year, €21.3m project to reduce European greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution from waterborne transport under Horizon 2020, the European Commission’s research and innovation programme.

The goal was to demonstrate that it was possible to design a fully electric, emission-free, medium-sized ferry for passengers and cars, and develop a model that could be used elsewhere.

Industry estimates suggest that Ellen, a collaboration between mostly Danish researchers, public authorities and private companies, could replace up to 900 ferries across Europe.

But the prototype faces an uphill battle for widespread rollout because of the need to build the ships from scratch, the lack of infrastructure at ports, the rise of biofuels, and a political focus on emissions targets only for vessels larger than 5,000 tonnes.

Ellen is powered by one of the largest batteries ever installed for maritime use, with electricity converted from high-voltage AC to DC at the charging point and converted back to AC at the propulsion motor. This propulsion system, designed by a Finnish-based subsidiary of Danish engineering group Danfoss, is used in electric cars but is rarely found in maritime engines and loses only eight per cent of the power from charge to conversion.

In an interview with The Parliament, John Wind, senior sales manager at Danfoss Editron, pointed out that a further five per cent is lost during the conversion from the AC grid to the DC battery on board. “This means that, in operation, the ferry has 87.4 per cent energy efficiency in the electric system, which is more than twice that of the propulsion system of a diesel ferry.”

The ferry’s exterior is also hyper-focused on energy efficiency. “Ellen was designed to be long, narrow and lopsided when empty, making its shape more like a classic sailing yacht than a ferry,” says Wind, adding that they’ve already received orders for 20 copies of the e-ferry model. “The streamlined design reduces friction and drag, making Ellen more energy efficient.”

Ellen, the world’s longest range all-electric ferry

Ellen, the world’s longest range all-electric ferry

Ellen is operated by Ærøfærgerne and is currently used primarily by commuters from the southern Danish island of Ærø to the mainland, as well as tourists.

Ellen’s electric power comes from surplus renewable wind energy generated on Ærø. The charging station is connected to the mainland via undersea cables as a backup source of power. “The ferry is charged for 20 minutes at [the port town of] Søby on Ærø after each trip from the mainland and for another 40 minutes during a break over lunchtime,” says Ellen ferry captain and Ærø resident, Thomas Larsen.

Ellen has no emergency generator on board, making the vessel the first electric ferry to be built without backup power – something that does not phase Captain Larsen, who says he would drive an Ellen e-ferry model through the narrow Bering Strait, provided the ship had enough battery power on board.

In June 2022, Ellen set a record for the furthest distance travelled by a fully electric ferry, sailing 50 nautical miles on a single charge. Other existing electric ferry models travel only short distances – the Ampere and MS Medstraum in Norway sail 20 and 30 minutes respectively, compared with Ellen’s 60 minutes.

But it’s not all roses. The Ellen model runs into issues because it requires building from scratch, and that comes with a price tag 40 per centthat of 40 per cent higher than building a diesel-powered vessel of the same size.

Payback for electric ferries hovers around four years and operating costs are 24 per cent lower than a diesel alternative, but investment for new builds remains elusive due to the high upfront cost.

If the Ellen e-ferry model is to spread across Europe, ports will have to invest in building new infrastructure with the capacity to charge multiple ferries every day

Instead, many diesel ferries have been refitted with battery power as well as fuel on board. These hybrids can travel longer distances than fully electric ferries and are able to visit ports that do not yet have charging infrastructure, while simultaneously applying pressure to those ports to support electrification.

Many ports lack both the grid infrastructure to bring the electricity to the dock as well as the space, cables and connectors involved in charging the ferry. In the case of Ellen, the charging station on Ærø was purpose-built at the Søby dock, where there was space.

The Søby charging station may in future also be used by a pair of ferries, operated by Ærøfærgerne, twice the size of Ellen set to sail between Faaborg and Søby, the primary route for lorries carrying food and other supplies to Ærø. This is, however, a small port village frequented by only one (but soon three) electric ferries.

If the Ellen e-ferry model is to spread across Europe, ports will have to invest in building new infrastructure with the capacity to charge multiple ferries every day. Hamburg and Antwerp are among the top candidates for ports that will become vanguards of maritime electrification.

In December 2022, Hamburg announced it had ordered three hybrid plug-in ferries using the same Danfoss Editron propulsion system and shore connection used for Ellen. Meanwhile, Antwerp introduced its first electric ferry – named Op Stroom – in December 2022, with the capacity for 150 passengers and 75 bicycles.

Both cities have focused on domestic services primarily used as public transport, but the same issues with port infrastructure also crop up for international routes, such as the Calais or Dunkirk to Dover route between France and the UK.

“Ports must become energy hubs. If there is no clean energy, there will be no clean transport”

Ports, local authorities and maritime transport companies will need to work together to tackle the lack of electrification infrastructure at ports. By 2030, maritime ports in the EU which see at least 50 port calls by large passenger vessels, or 100 port calls by container vessels, will be required by the Commission to provide onshore power supply for such vessels.

A spokesperson for the Commission says this requisite and an additional zero-emission requirement at berth for passenger ships and containerships “will create the necessary demand to justify onshore investments in the necessary port infrastructure”.

Ports will also need to develop the infrastructure for alternative fuel sources such as biodiesel and other biofuels, although concerns have been raised over whether these are genuinely better for the climate.

“Ports must become energy hubs,” says Dr Mikael Lind, senior research adviser at Research Institutes of Sweden. “Their role as energy hubs in the energy transition is critical. If there is no clean energy, there will be no clean transport.”

Biofuels represent a much smaller deviation from the fuels currently in use, such as diesel, and it is thought most of them will be compatible with diesel ship engines. Biofuels are also, currently, the primary option for deep-sea shipping to become more climate friendly, even if they are less energy efficient than electric alternatives and produce emissions.

That’s because electrification isn’t technically or economically feasible for deep-sea shipping vessels. Long-distance deep-sea shipping uses vast amounts of fuel. Switching to electric would mean switching fuel tanks for batteries, which are heavier and require much more space. The extra weight from and space taken up by the batteries would mean less room for cargo.

For the foreseeable future, therefore, combustion engines will remain relevant as energy conversion systems. Ports, therefore, will need to adjust to provide cleaner fuel sources for deep-sea ships, as well as building infrastructure to support charging electric vessels.

But while the Ellen model was never intended to replace deep-sea cargo ships, biofuels are not necessarily the best answer for short-haul ferries. Biofuels are intended to reduce the carbon intensity of industries, such as deep-sea shipping where electrification is not viable.

“The different propulsion options that are considered for ships depend on the type of route they are taking. Ferries operate regular and shorter routes so electrification is a viable option, providing the infrastructure is set up, but we would not use batteries for long-haul shipping,” says Dr Lind.

Ferries in Italy produce by far the most carbon dioxide emissions in Europe, with Greece coming in at number two

However, the biggest barrier to the rollout of electric ferries in Europe may be European lawmakers’ focus on emissions targets only for vessels heavier than 5,000 gross tonnes. These ships account for around 90 per cent of global emissions from maritime transport, but only 55 per cent of vessels that dock at EU ports.

This means that EU maritime transport emissions targets exclude 45 per cent of ships docking in its ports. The FuelEU Maritime deal agreed in March between the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union focuses solely on vessels over 5,000 gross tonnes. The deal stipulates that emissions must be reduced by two per cent from 2008 levels by 2025 and 80 per cent by 2050. There are no targets for short-haul ferries.

The Commission tells The Parliament it will reassess the functioning of the FuelEU Maritime in 2027, including considering extending the scope of the targets to ships lighter than 5,000 tonnes.

The need for action on maritime transport emissions is particularly great in southern Europe. Ferries in Italy produce by far the most carbon dioxide emissions in Europe, with Greece coming in at number two, according to a 2022 report from Siemens Energy. Italy and Greece, along with Germany and the UK, are responsible for more than 35 per cent of European ferry emissions between them – but going electric would reduce the emissions by around 50 per cent, according to the report.

The solutions already on the table – full electrification of shorter routes, onshore power build-out and hybridisation of all routes – suggest a great untapped potential for the ferry industry.

Ferry operators in the United States, New Zealand and India are taking advantage of electrification technology as part of their commitment to decarbonisation – is it time Europe caught up?

“From my personal view, a higher focus should have been laid on short-haul transport, such as ferries, and including transport between European ports, not only deep-sea shipping,” MEP Paulus says. “Unfortunately, my co-negotiators felt much more reluctant and were afraid this would increase ferry prices.”

Paulus warns that the deal might discourage operators from moving towards electrification, despite the evidence of Ellen’s success, and describes the electrification of Europe’s ferries as a chance to “future-proof the maritime transport industry and carve out a competitive advantage by developing the technologies that everyone is going to want in 10 years’ time”.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.