The results of the European Parliament elections in early June look like good news for Ukraine. The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) came out on top with 189 seats, a gain of 13, according to provisional results. That puts European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, a strong backer of Ukraine, in a good position for a second mandate.

Groups to the right of the EPP also made gains, and there the picture for Ukraine is more mixed. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group – home of Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party – is broadly united in its support for Ukraine. But many independent parties and those in the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) group are friendly to Russia or want an end to the European Union’s financial and military support.

Far-right parties are unlikely to be strong enough to cause a change in direction, says Svitlana Taran, a research fellow at the European Policy Centre. She describes them as “white noise that may get louder,” but says “they will not have decisive power to [make] some recommendations or to adopt some decisions or resolutions that will be anti-Ukrainian or pro-Russian.”

Things could look different in the longer term if far-right parties gain influence over national governments, says Žiga Faktor, deputy director of the Prague-based Europeum Institute for European Policy. This would be “much more dangerous for the general support of Ukraine than the slight strengthening of the positions of the far right within the Parliament,” he says.

French President Emmanuel Macron called snap elections after Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN), part of the ID group, strongly outperformed his own coalition in the EU elections. A similar result at the national level could lead to the RN’s Jordan Bardella – the party’s lead candidate for the EU elections – becoming prime minister. Such a development would be sure to constrain Macron, currently one of Ukraine’s most vocal supporters.

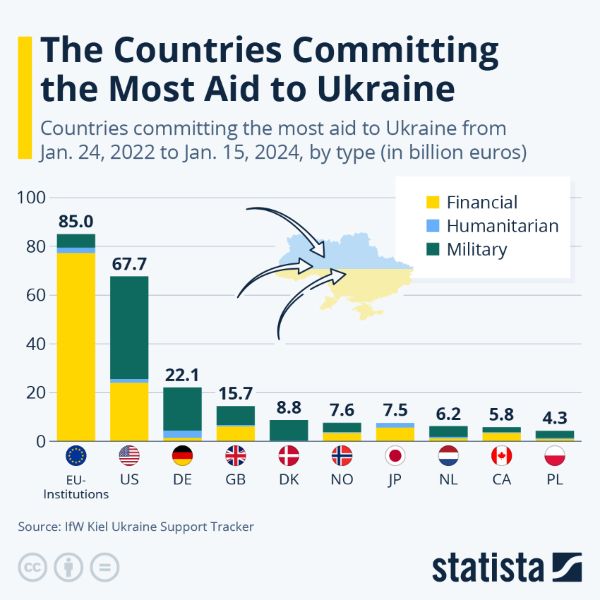

The EU institutions are the single biggest donor to Ukraine, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy ‘Ukraine Support Tracker.’ They sent about €85bn in financial, humanitarian and military aid between 24 January 2022 and 15 January 2024, ahead of the United States which sent €67.7bn over the same period.

The EU’s current multiannual financial framework (MFF), which runs until 2027, provides a solid base for the coming years, Faktor says. The MFF includes the Ukraine Facility, worth €50bn over the period 2024 to 2027.

Taran suggests that more funds should be directed to the Ukraine Facility to support reconstruction and its budget. But this would have to be decided by the new leadership of the European Commission and approved by the Council.

Expanding trade opportunities

Besides direct support, the EU can also help Ukraine by facilitating trade, particularly of agricultural exports – but this is also complicated, not least due to powerful farming lobbies that may feel emboldened by the EU’s rightward shift. Farmers in Poland and other countries have, since last year, protested the influx of cheap Ukrainian grain into the EU market.

The EU introduced so-called autonomous trade measures (ATMs) for Ukraine after the Russian invasion, effectively suspending tariffs for its exports. But these are coming under increasing pressure: while being extended this year for the second time, a provision was introduced that allows for the reintroduction of tariffs once some agricultural products surpass a certain amount.

Even with this “emergency brake” several countries including Poland and France were hesitant to prolong the ATMs at a first meeting in March and negotiated a stricter barrier for agricultural products. The final version could mean a loss of around €350m a year for the Ukrainian economy, says Nazar Bobitski, director of the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club’s Brussels office.

As for next year, Faktor predicts there may be another round of bargaining and perhaps further exclusions and limits, but these ATMs will eventually be extended.

Still, the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club advocates for a long-term bilateral trade agreement, arguing that the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, which entered into force in 2017, “offers a clear path.”

It’s the Commission that will lead the consultations on the EU side. “I expect these consultations to begin soon as they should be completed well before June 2025,” the EPC’s Taran says. “However, it might be difficult to reach an agreement on this during Hungary’s presidency.”

Joining the club

Ukraine’s eventual goal is to achieve full EU membership. It submitted an application in February 2022, days after Russia’s full-scale invasion.

The process is a long one, but it should move forward in the next mandate because political groups that have expressed support in principle for Ukraine accession – the EPP, Socialists & Democrats (S&D), Renew Europe and the Greens/EFA – hold a combined 457 seats, a clear majority in the 720-seat Parliament.

“Those people and those parties that were actually driving the process within the Parliament will remain the same, which is definitely a good sign,” Faktor says.

The member states’ ambassadors also agreed in mid-June “in principle” on the negotiating frameworks for the membership talks with Ukraine and its neighbour Moldova.

Nevertheless, there are many steps along the road, any of which can quite easily be blocked. “Officially opening the accession talks is just the first step along 50, 60, 70 decisions that have to be taken unanimously,” Faktor says. In other words, any one national leader – Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, for example – can block the process at any stage.

The EPP and its constituent parties in member states always have been perceived in Ukraine as the staunchest supporter of Ukraine since the beginning.

The looming national elections in France could be another matter of concern, Taran says: “It would be more difficult, of course, to deal with two Hungaries in the EU,” she says, referring to the possibility Le Pen’s party could make significant gains this summer.

Overall, Ukraine can be tentatively optimistic about the outcome of the elections, the experts agree, especially if Von der Leyen wins a second mandate – which the Parliament is due to vote on in Strasbourg on 18 July.

“Von der Leyen was also the one bringing up this idea of creating a different portfolio for a defence commissioner,” Faktor says. “Von der Leyen is the best-suited candidate to really support it and to go further with it because it's her vision.”

Bobitski, from the agricultural lobby, says that Von der Leyen is very popular in Ukraine for her efforts so far to mobilise support from the EU.

“The EPP and its constituent parties in member states always have been perceived in Ukraine as the staunchest supporter of Ukraine since the beginning,” he says.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.