Are you feeling the mounting pressure of the Christmas season, wondering what gifts to get your loved ones? In Iceland, you would not struggle. On the island in the North Atlantic, books are the go-to present – thanks to a unique cultural custom that has been kept alive throughout the decades.

The cherished tradition carries a poetic name, Jólabókaflóð, which roughly translates in English to ‘the Christmas book flood’.

Every November, Icelandic publishers release hundreds of new titles at once, providing an eclectic choice for the gifting season. The tradition dates back to World War 2 when books emerged as the most beloved Christmas presents when, in contrast to other materials, paper was not rationed. “For most publishers, the Christmas market accounts for 70 to 80 per cent of annual revenue,” explains Helga Ferdinandsdóttir, project manager at the Icelandic Literature Centre.

It’s the most important time of the year for authors. Everyone is fighting for attention

Today, the book flood doesn’t just involve a myriad of new releases, but also a multitude of readings and events. One of them is the annual book festival held in Harpa, the concert hall, conference centre and major architectural landmark in the capital Reykjavík, which has been a Unesco City of Literature since 2011, a title awarded for best literary practices.

“It’s the most important time of the year for authors. Everyone is fighting for attention. They are really busy, presenting their books, visiting institutions, companies, and other places – wherever they want to read,” says María Rán Guðjónsdóttir, vice-chair of the Icelandic Publishers Association and founder of publishing house Angústúra.

The torrential downpour of books flows into the so-called Bókatíðindi, a catalogue of titles released by Icelandic publishers during the year. The 2023 edition has 650. While a printed copy used to be delivered to every household, it is now on sale in bookshops and supermarkets, and can also be accessed digitally.

“Books have a special place for us. A lot of children have them on their wishlists. Kids will go through the catalogue and get excited and mark the ones they want to receive. When I was a child, I did that too,” says Guðjónsdóttir. The tradition is here to stay, despite the many competing forms of entertainment at one’s fingertips today, she believes.

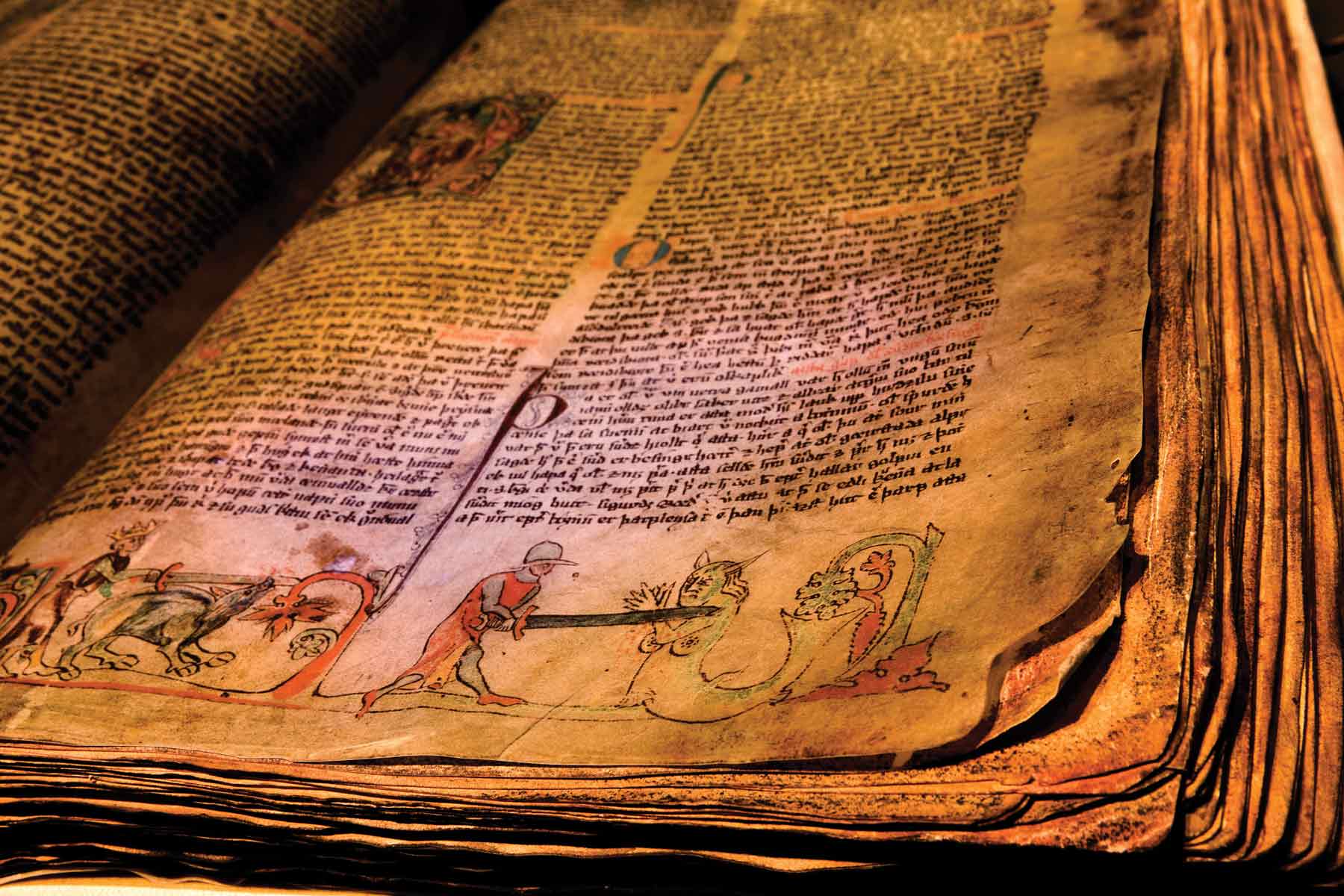

The birthplace of iconic sagas, written mostly during the 13th and 14th centuries, Iceland has a rich history of storytelling. During the long winter evenings, recounting tales of Viking voyages and family feuds was the main pastime, ensuring the legends went from generation to generation. “That is where everything begins for us, our literature, our history and our identity,” writes Maríanna Clara Lúthersdóttir, lecturer in comparative literature at the University of Iceland. During these evenings of telling stories, known as kvöldvaka, children were also taught to read and write.

Interestingly, Iceland has one of the highest literacy rates in the world and a reputation for publishing more books per capita than any other country. One in three Icelanders read books daily, and many write themselves, reflected in the old saying “að ganga með bók í maganum” – everyone “has a book in their stomach”. It come as no surprise that one in 10 will publish a book during their lifetime.

While literature has always played a significant role in Iceland, it took a while for the homegrown talent to be noticed abroad. Halldór Laxness, who won the Nobel prize in 1955 for Independent People, put modern Icelandic literature on the map. It is a masterpiece of social realism, skilfully interweaving the struggle of poor Icelandic farmers in the early 20th century with capitalism critique and the vivid description of life in an inhospitable landscape.

Originally published in 1934, it became one of the first Icelandic novels to be released abroad. Today, Icelandic books are being translated into about 50 foreign languages and, according to the Icelandic Literature Centre, the number of translations has almost doubled over the last 10 years.

Nevertheless, even the country of bookworms is affected by changing currents. “Like elsewhere in Europe, Iceland is seeing dramatic changes in the book market. There is a lot of discussion regarding the impact of streaming subscriptions, technological changes and the changing consumption habits of book and culture consumers,” says Ferdinandsdóttir. “For example, there are fewer big publishers than before, but we can see that smaller publishers and micro-publishers are thriving at the moment.”

Adding the perspective of a mid-sized publisher, Guðjónsdóttir says: “It is a difficult business. There are now fewer copies behind the titles on the bestseller list, and audiobooks are changing the market.”

But with literature constituting such an essential element of Icelandic cultural heritage, the government has stepped in to help, providing a funding programme allocating ISK 400 million (about €2.6m) per year, which Guðjónsdóttir compares to initiatives that have long been in place in the film industry.

While the book flood means an especially pleasurable time for readers, who find a diverse selection to rummage through, there’s a lot at stake for the book business. “Publishers are under quite a lot of pressure, in the sense that they need to be successful,” says Guðjónsdóttir. “The books need to be ready for printing no later than August, and from then on it’s a very, very hectic time.”

Ferdinandsdóttir weighs in: “The Christmas book flood brings both pros and cons for booksellers. The ebb and flow of sales can make it difficult for bookshops to manage, with an influx of staff and resources in the months leading up to Christmas followed by slower months at the beginning of the new year.”

It’s better to be without shoes than to be without a book

The deluge grows so sizable that in the months leading up to Christmas, books cannot only be found in bookshops but also stream into supermarkets and even petrol stations – making for truly trouble-free gift-buying.

“It’s just a very typical Christmas: on the 24th you open the presents, you have a nice time together, and then you crawl into bed in your pyjamas and read the books you received,” explains Guðjónsdóttir. “Some people will stay up all night reading because the books are so good. It’s like a reading holiday. It’s so nice.”

Tides might be slowly turning, even in a literature-crazed country like Iceland – but reading and writing remain activities deeply ingrained in the national psyche. As an Icelandic proverb says: “It’s better to be without shoes than to be without a book.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.