The German town of Görlitz and the Polish town of Zgorzelec share more than just a border. A close friendship, which stretches back decades, is evident today in how easily pedestrians can walk from one to the other. It’s a quick hop over the narrow Neisse River that divides the two sides.

Going by train, however, gets more complicated.

Poland completed electrifying its track in 2019, fulfilling its end of an agreement. Germany did not. That means only slower and more polluting diesel trains can continue westward onto Dresden, forcing passengers to change trains, which adds time and hassle to the journeys.

The muddle is emblematic of difficulties repeated throughout the European Union's rail network. Lack of coordination among national systems, subsidies that tip the scales in favour of other modes of transport, and complicated ticketing processes that lack consumer protection are among the issues delaying the arrival of the EU's train travel dreams.

“We have the capacity to make existing infrastructure so much better,” Robin Loos, deputy head of energy, transport and sustainability at BEUC, a European consumer organisation, told The Parliament.

Partly as a result of these shortcomings, flying remains the preferred choice for many travellers in the EU, especially for longer journeys. While both air and rail passenger traffic has mostly returned to pre-pandemic highs, there is still a significant mental gap when consumers weigh up which way to go. Air beats out rail on perceptions of price, time and reliability, according to a 2019 Eurobarometer survey.

Trains only win on climate considerations, but the lower carbon footprint on its own does not appear enough to get more people to make their trips by train.

Air vs. rail

“The EU has adopted climate targets, and we have committed to the Paris Agreement,” Lorelei Limousin, senior climate and transport campaigner at Greenpeace EU, told The Parliament. “Shifting to rail from air and from roads is really key to achieving this.”

A 2023 study for the European Commission found that switching from plane to train for routes where both modes are easily available could result in a 17% drop in CO2 emissions. Along shorter routes, such as between Paris and Brussels or Florence and Rome, going by train is significantly faster than flying.

Flights in the EU contributed to as much as 4% of the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, according to the Commission. Globally, aviation emissions could triple by 2050 over their 2015 levels.

In hopes of making a dent in that, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has proposed a digital “one stop shop” for rail bookings. It would allow consumers to buy a single ticket across the EU. The project is meant to support the Green Deal's goal of doubling high-speed rail traffic by 2030 and tripling it by 2050.

A single, EU-wide booking system could also improve competition and price by helping smaller and privately run railways gain exposure. Currently, most ticketing is done by a state’s dominant rail company, such as Germany’s Deutsche Bahn or France’s SNCF, giving these mostly public monopolies an advantage.

Smaller ventures have struggled to compete, such as Germany’s Hamburg-Köln-Express, which began in 2012 but stopped in 2018.

“We had the trains. We had the slots. We had the station access. But no one knew we were there,” Nick Brooks, a former employee of the train company and now secretary-general of AllRail, an association of independent passenger rail, told The Parliament.

Ticketing delays

Though a spokesperson told The Parliament that the Commission is working to "harmonise rules" that makes cross-border train travel easier, its single-ticket plan has barely left the station. Rather, it's a carryover from Von der Leyen's first mandate, where it made little progress.

“Other topics took precedent,” Limousin said. “There was not enough political will to really make it happen.”

Von der Leyen’s second term presents a new opportunity for a second try. She has instructed her Commissioner-designate for Transport, Apostolos Tzitzikostas, to use EU funds to support sustainable and interconnected transport networks. The ticket system makes an appearance in her political guidelines, as a way to simplify train bookings and provide passengers with a uniform set of consumer protection regulations that covers their entire journey.

At present, passengers travelling across EU borders with more than one national train company can face a whack-a-mole of rules when things go wrong. It can be difficult to hold anyone accountable.

“If the moment you book your ticket to the moment you arrive at your destination is good, even if it’s slow, that’s a massive improvement for many people,” said Loos.

A better experience addresses just part of reluctant travellers’ concerns. A recent study by BEUC found that the most important factors when choosing a mode of travel are comfort, frequency of service and price.

To get at those factors, EU policymakers will need more than a single ticketing system. Research by Transport & Environment, an environmental group, shows that in 2022 airlines saved over €34 billion in the form of tax breaks on VAT and fuel tax.

“It’s a non-level playing field,” Mark Smith, the founder of the popular train blog, The Man in Seat 61, told The Parliament

Investing in rail infrastructure

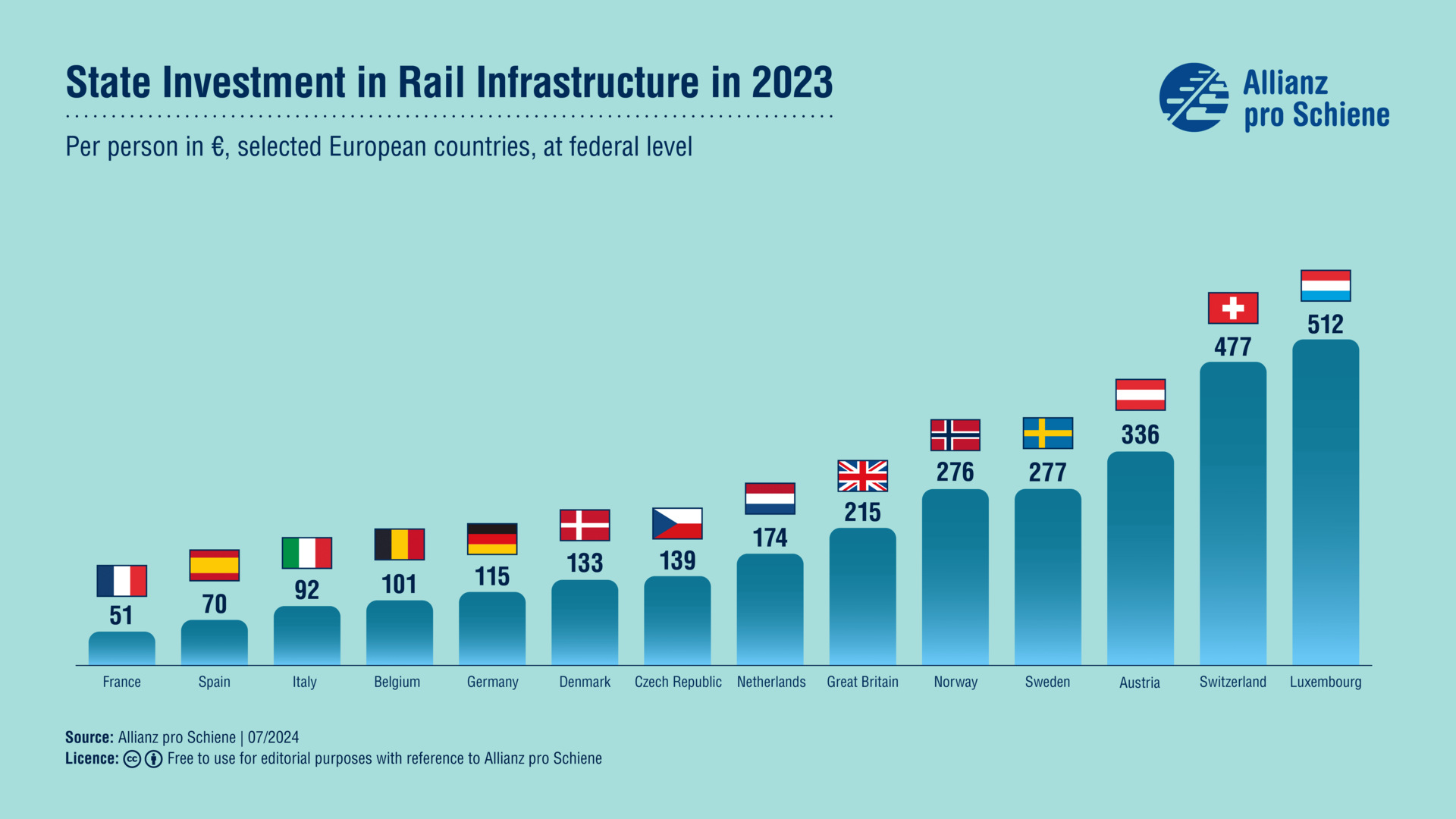

EU and external studies show that improved service and faster trains can encourage more people to go more places by rail. That costs money, and investment varies across the bloc. Austria, for example, has the highest number of frequent train travellers of any EU member and invests among the most of any country in the visa-free Schengen Area.

France banned short-haul domestic flights last year along routes where a rail alternative existed. Both the airline industry and environmental groups panned the regulation, respectively arguing it was unfair and ineffective.

"The modal switch will of course ultimately depend on the consumer's choice, and it is our duty to work together towards creating an equally competitive and resilient railway transport sector,” Elissavet Vozemberg-Vrionidi, the chair of the European Parliament’s Committee on Transport and Tourism, told The Parliament.

Some of the problem lies not in building more, but in making more of what already exists. A report by Greenpeace released earlier this year found that direct train connections between major European cities could more than triple by using existing tracks. Of 990 routes analysed, 69% had direct flights, whereas just 12% had direct train connections.

The EU's mishmash of 27 national operations can get in the way of a more cohesive train ecosystem. In 2022, the German antitrust authority investigated Deutsche Bahn for refusing to share information outside of its online booking system. DB said the practice made the process more efficient, but doing so made it more difficult for lower-cost operators like Flixtrain.

“They would sooner share data with no one than share data with private rivals within their own country,” independent rail analyst Jon Worth told The Parliament.

Another private operator, European Sleeper, is also beholden to the whims of a disjointed market dominated by state-backed players. In a recent statement, the company that runs two night-train routes across Europe said it was “facing uncertainty” about schedules for 2025 due to “lack of coordination between Germany and neighbouring countries.”

“You have to have the old way of running state-run railways in the interests of passengers, or we are encouraging competition,” Worth said. “What we've got at the moment in most of Europe is the worst of both of those worlds.”

This story has been updated to include comment from the European Commission.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.