Treating Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse as a Global Health Emergency: A Call to Action for European Leaders, writes Paul Stanfield, CEO of Childlight Global Child Safety Institute

The world is in the grip of a pandemic that rarely make headlines but devastates millions of lives — child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA). This is not just a law enforcement issue; it is a global health emergency, and we must approach it with the same urgency, dedication, and resources we would any public health crisis.

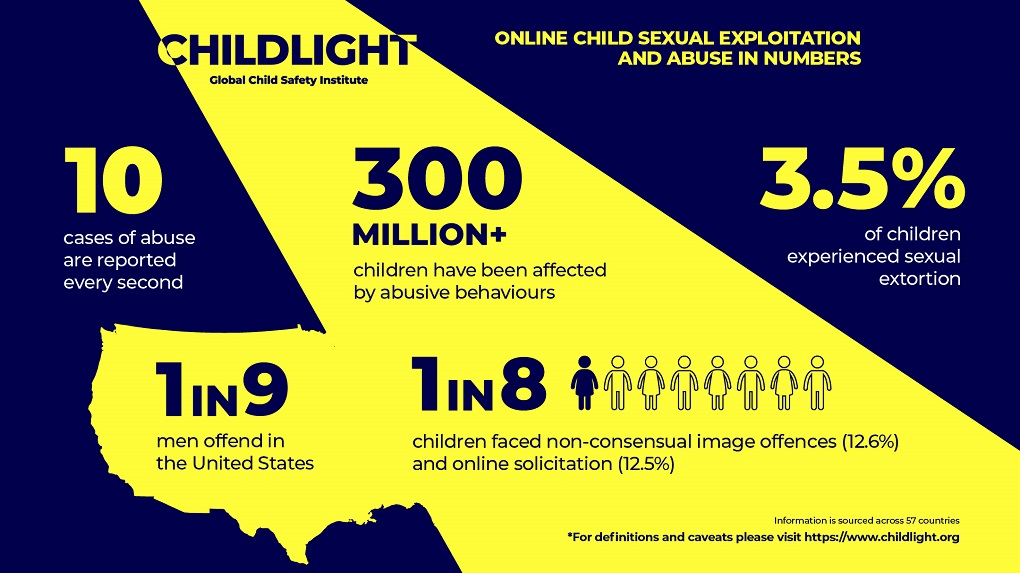

At Childlight, hosted by the University of Edinburgh and established by the Human Dignity Foundation, we recently produced the world’s first global estimate of the scale of online CSEA. The results are harrowing: around 10 children fall victim to online sexual exploitation and abuse every single second. This is not just a statistic — it represents real lives, young people robbed of their childhoods, their mental and physical health permanently scarred.

However, what we currently know is likely just the tip of the iceberg. Across Europe, as in many regions of the world, the data on CSEA is incomplete, currently making it impossible to grasp the full scale of the problem. This lack of comprehensive information impedes our collective ability to respond effectively. How can we tackle a pandemic if we do not understand its true scope and nature? That is why I am urgently appealing to you, policymakers and officials across Europe, to help us gather and compile country-level CSEA data to make our research next year more complete. With accurate data, we can begin to shine a more powerful light on this crisis and work towards meaningful preventive solutions, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 16.2.

While we applaud the European Parliament and governments for the progress already made in creating a safer online environment for children, the hard truth is that much more remains to be done. With the rise of emerging threats such as AI-generated child sexual abuse material (CSAM), grooming, and sexual extortion, the problem has expanded beyond the capacity of law enforcement agencies alone. The scale is simply too vast.

To effectively confront this crisis, we need a radical shift in approach. Just as we learned with other global health emergencies, prevention must be at the heart of our response. A public health approach to CSEA would prioritise preventive measures, education, early intervention, and victim support. It would demand coordinated action across sectors—health, education, technology, and law enforcement—backed by solid data and evidence-based strategies.

I urge you to act, and to act now. We estimate that over 300 million children are living in the darkness of exploitation and abuse every year. They cannot wait for incremental change. If you can help us collect the vital country-level data we need, or if you are willing to work with us to create a safer world for children, please reach out to me directly at paul.stanfield@ed.ac.uk or our director of data, Professor Deborah Fry, on debi.fry@ed.ac.uk. Together, we can all make a difference. But we must move quickly — because children cannot wait.

As we revise the CSA directive, we must recognise that a holistic approach is key to ending Child Sexual Abuse, writes Saskia Bricmont MEP, co-ordinator for the Greens/EFA on the LIBE Committee

As we revise the CSA directive, we must recognise that a holistic approach is key to ending Child Sexual Abuse, writes Saskia Bricmont MEP, co-ordinator for the Greens/EFA on the LIBE Committee

To effectively combat child sexual abuse and exploitation (CSA), the CSA directive, currently under revision, needs to evolve toward a more holistic approach including criminal justice’s response but also enhanced prevention and public health aspects. While current measures focus on criminal law responses, a proactive strategy that integrates data-driven insights, cross-sector collaboration, and community resources, is essential in reducing CSA incidence.

The crucial update to the directive needs to include systematic data collection across EU member states to better understand CSA’s prevalence and risk factors. By establishing coordinated national systems and partnerships with health and social services, key insights can be gained into environments, demographics, and behaviours that increase the risk of abuse.

Prevention efforts also need to prioritise early education programs in schools, family services, and healthcare, focusing on personal boundaries as well as affective and sexual education, digital literacy, recognising abuse indicators and working on preventing abuses from the perpetrators. Implementing such programs across the EU will ensure children are equipped with knowledge to protect themselves. Early intervention programs in Sweden for instance help to reduce abuse cases, as informed children are better positioned to seek help if needed.

An indispensable component of a preventive model is cross-sector collaboration, including cooperation with police and justice services. Belgium’s Child Focus initiative provides a valuable example, working with law enforcement to support rapid response, facilitate investigations, and prevent abuse through community engagement. Integrating similar models across EU countries could significantly strengthen the directive, as seamless coordination between police and social services can help identify and intervene in at-risk situations before abuse occurs.

Adopting the Barnahus (Children’s House) model, successfully used in countries like Iceland, is another way the directive could evolve. This model brings together medical, psychological, social, and legal support under one roof, offering a comprehensive, victim-centered response that reduces trauma for young victims. The directive should encourage adoption of the Barnahus model, which fosters child-friendly environments where recovery and judicial processes are managed compassionately. As responsible MEP for the Greens/EFA on the revision of the directive, I consider that child-friendly justice provisions across the text are crucial.

Given that much CSA now occurs online, strengthening digital safety measures, including safety by design, is paramount. Regular research on evolving digital abuse methods will ensure protections remain robust and forthcoming legislation on digital fairness will hopefully ensure better for minors online.

By integrating a data-driven, collaborative, and preventive public health approach—alongside models like Child Focus and Barnahus—the directive can shift from reactive to proactive measures, creating a safer environment for children and focusing on preventing abuse before it happens. I very much hope we will be able to strengthen provisions to protect children and that we will share a high degree of ambition for this directive.

Saskia Bricmont MEP is co-ordinator for the Greens/EFA on the LIBE Committee

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.