“Hungarian TV rarely broadcasts your games, but because of you I try to watch when I can.”

Union Berlin midfielder András Schäfer, the recipient of this compliment, looks a little embarrassed as he replies: “Thank you very much.”

The 23-year-old Hungarian has had a meteoric rise. Within the space of 18 months, he’s gone from relative obscurity in the Slovakian top division to scoring for his country against Germany in the European Championships, and becoming a mainstay of a Union side battling with Bayern Munich at the top of the Bundesliga.

“You’re looking good,” comes another compliment.

“Thank you very much,” Schäfer says again, explaining he’s put on seven kilos of muscle since moving to Germany.

The back-and-forth is jovial and good natured, and why wouldn’t it be? Schäfer’s interlocutor often finds himself cosying up with Hungary’s star footballers. Balázs Dzsudzsák, Hungary’s most-capped player of all time, counts him as a friend.

The interlocutor in question? Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

This exchange can be seen in a video that Hungary’s controversial premier posted on Facebook last October, on the same day he met with Schäfer in Berlin. Within hours of his post, which racked up nearly 8,000 likes, Union Berlin issued a statement defending the meeting.

“There was an official letter from the Hungarian Embassy asking for a private meeting with a Hungarian national player,” stated Union’s head of communications, Christian Arbeit. “We complied with this request. We didn’t receive him officially.”

For Orbán, his visit to Union in October was the first time he’d ventured west with his increasingly regular ground-hopping photo ops.

Just a few months earlier he had been to watch games at Sepsi OSK and FK Csíkszereda, two ethnic Hungarian sides in Romania’s first and second division, alongside Hungarian national team manager Marco Rossi and an adoring crowd. Orbán is also a regular at Hungarian national team matches and domestic games within Hungary.

As Hungary has become increasingly more competent on the world footballing stage, there is no denying the political benefits of photo ops have also multiplied. But there is also little doubt that Orbán’s love for the game is genuine.

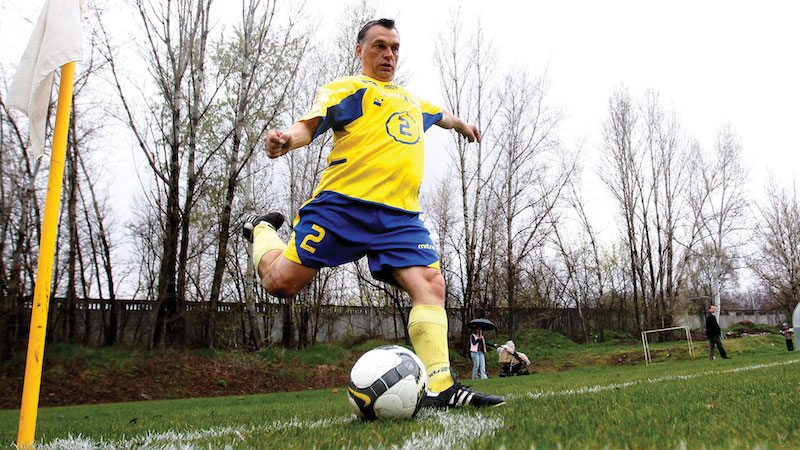

According to an article in The Guardian from 2018, Orbán hadn’t missed a single Champions League or World Cup final for 20 years. He was also a decent footballer himself, floating around Hungary’s fourth and fifth tier before officially retiring in 2005 – even playing full competitive games while sitting as Prime Minister after his election in 1998.

Viktor Orbán kicks a corner in a 2010 football tournament | Photo: REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo

Viktor Orbán kicks a corner in a 2010 football tournament | Photo: REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo

“It is difficult to gauge whether politicians do something for politics, or their heart is, indeed, in it,” Gergely Marosi, a sports journalism lecturer at Budapest Metropolitan University tells The Parliament. “But in this case, I am quite sure Orbán’s love for the game is real. He is a genuine football fan, and he is also a former lower-league player. Football definitely shaped and influenced his life and how he thinks.”

Orbán’s love of football is arguably one of the main reasons he has been able to see opportunity in the game where his political opponents have not, and cynically leverage that opportunity for his own benefit.

It is estimated the Hungarian government has spent as much as €2bn on football within Hungary and in neighbouring countries with ethnic Hungarian communities since Orbán regained power in 2010. Plenty of detractors have voiced their concerns since day one, and while the project is by no means an unqualified success, the wins have been notable.

On the pitch, Hungary has qualified for two major tournaments since 2010, a feat it hadn’t achieved since 1986. The national team beat England 4-0 last June to outdo the storied 6-3 victory of the “Magical Magyars” – the legendary Hungarian football team of the 1950s – over the English. And even at club level, Ferencváros’s recent successes have been historic.

But it’s off the pitch where the wins are more impactful, though less apparent and less measurable. Opponents could quite rightly point to figures showing that 12 per cent of Hungarians were at risk of living in poverty and around 75 per cent of the total population live below the European Union poverty threshold, and ask why there is such lavish spending on football. Yet Orbán is a political leader whose success comes in the form of consolidating power, and football has undoubtedly played its part in that.

“Football – its tribalism, its myths and rites, the atmosphere of the locker rooms, the ‘us – a team – against the world’ attitude – might have well shaped his politics and how he sees politics,” says Marosi.

“Football – its tribalism, its myths and rites, the atmosphere of the locker rooms, the ‘us – a team – against the world’ attitude – might have well shaped his politics and how he sees politics”

He continues: “It might have directly influenced some of his actions. And he also shaped football to fit his politics: he knows very well how popular football is in Hungary, he knew very well how underfunded and run-down it used to be, infrastructure-wise. So channelling a lot of money into football and sports in general wins over people, both directly – people working in sports – and indirectly – people who’d appreciate an upswing. And of course, he looks at football as something closely tied with national identity and pride, both very important to him and his politics.”

Football is also a useful tool for boosting national identity and pride outside of Hungary. The trip to Romania wasn’t just a photo op, it was a chance to connect with ethnic Hungarians in the region. Pushing money into the local economy, community and football clubs in the ethnically Hungarian areas of Romania – an approach repeated in Ukraine, Slovakia, Serbia and Croatia – increases the odds that Hungarians abroad who can vote in national elections in Hungary will support Orbán at the polls.

Another element rarely discussed is the impact of having Hungarian footballers like Schäfer on board. As the Fifa World Cup 2022 unfolds in Qatar, we’ve seen how footballers can shape the discussion of issues off the pitch, with Iranian players refusing to sing their national anthem and German players covering their mouths for a team photo in protest at Fifa’s decision to ban pro-LGBTQ+ armbands.

Yet when Hungary’s national team goalkeeper Péter Gulácsi wrote a social media post supporting an LGBTQ+ charity in 2021, he was lambasted by political figures and fans alike. No one has dared speak up on the issue since.

By actively cosying up to footballers, Orbán is doing his best to ensure there will be more footballers like Schäfer, through whom he can launder his image, than those like Gulácsi, and therefore fewer potential threats to the status quo from a powerful cultural force.

Sure, there is the ego boost that comes with being friendly with the most popular cultural figures in the country, which footballers are in Hungary. But Orbán’s love for the game has allowed him to see political opportunity where others haven’t.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.