When December rolls around this year, it might be the last time people in Denmark can easily participate in a beloved Christmas tradition: sending and receiving Christmas cards. That's because PostNord, the state-run national postal service, plans to stop delivering letters by the end of the year.

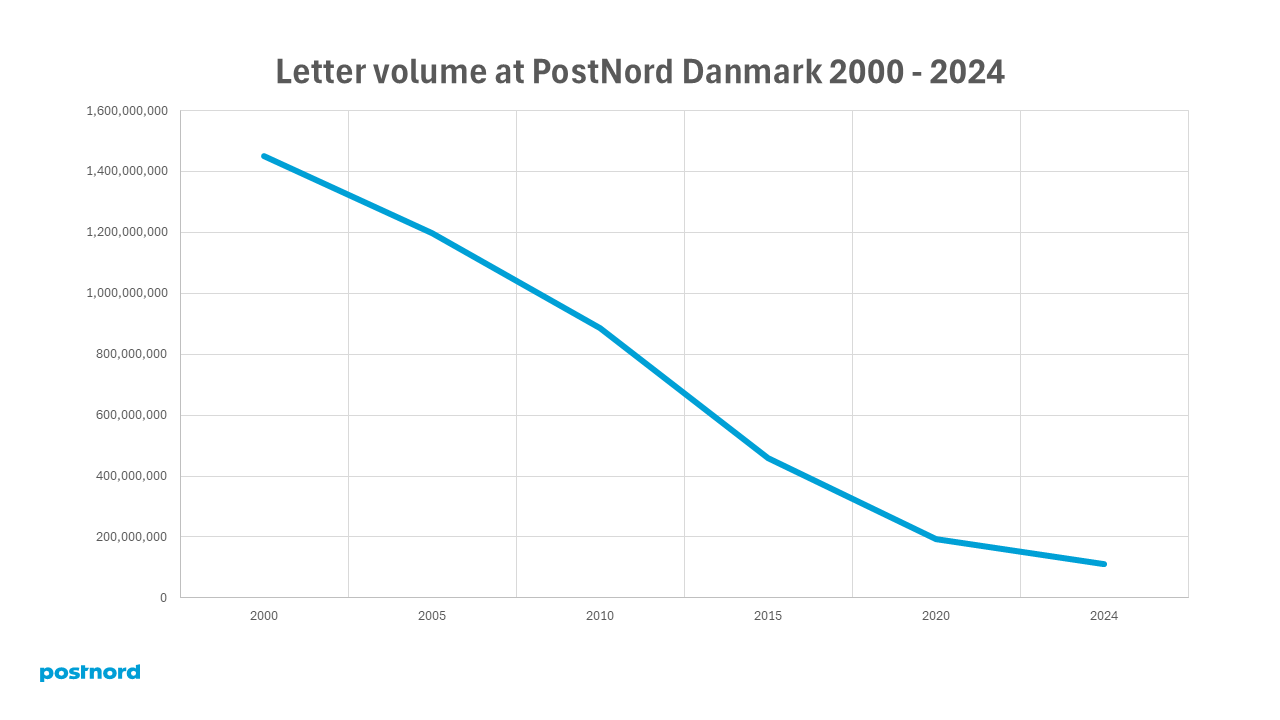

The decision reflects a 90% drop in letter demand over two decades. PostNord, owned jointly by the Swedish and Danish governments, has said it could no longer justify the cost of maintaining the service on the Danish side.

As one of the world's most digitalised countries, most people in Denmark have dwindling reasons to send paper through the post. Many government and other services are handled online.

Yet, Christmas cheer aside, it could put a small but vulnerable subset of society in trouble.

“It's not a given that you are able to be digitalised the rest of your life,” Marlene Rishøj Cordes, a senior consultant at the DaneAge Association, a nonprofit for senior citizens, told The Parliament. “Digitalisation is always changing.”

The people the post leaves behind

Some 270,000 people – around 4.5% of Denmark’s population – still rely on snail mail. This includes the chronically ill, the elderly and people with disabilities. These groups are already at risk of social isolation, and cutting mail service could add one more factor.

“When we think about communities helping older people, we should try to prioritise high-quality social contact,” Hans Rocha Ijzerman, director at the Annecy Behavioural Science Lab, told The Parliament.

Letter-writing advocates point to the death of the practice as a contributor to loneliness, which researchers and European policymakers are seeing increasingly as a public health problem.

The EU’s first-ever loneliness survey, conducted in the aftermath of COVID-19 lockdowns and social distancing, found more than one-third of respondents reporting feeling lonely at least some of the time. The report concluded that loneliness can reduce productivity and shorten life expectancy.

“Most of the people in my club are older people who can't get out. So letter writing is like a social thing,” Marjorie Edwards, who runs the UK-based Rainbows Penpal Club, told The Parliament. “Then there's also people who have mental health problems and don't want to go out and meet people, so having a letter is like having a friend. It helps them to connect.”

She called Denmark's decision “awful.”

From a state monopoly to a private one

PostNord's decision follows cutbacks and privatisation efforts at national postal companies around Europe, including Germany's Deutsche Post and France's La Poste. These have led to layoffs, stamp price increases, and a shift in business operations in hopes of riding the coattails of e-commerce giants like Amazon to profitability.

Since 2011, PostNord has been expected to compete with private-sector competitors, ending the company's mail monopoly. At the same time, it had to uphold its universal service obligation (USO) — filling any gap left in the market to ensure everyone in Denmark was served.

That changed with an amended postal act, which came into force last year. DAO, a private logistics company, is set to largely take over PostNord's services. Unions have criticised the shift, fearing job cuts and decreased service. Other critics worry that, with the public option out of the game and the private one cornering the market, prices will go up.

"They don't have to live up to the same old criteria for prices for the mail,” Cordes said.

As of now, a basic letter is slightly cheaper to send via DAO than PostNord. With the end of letter delivery on 31 December, PostNord will focus solely on packages, which the company says is more profitable.

“We are prioritising to be where the Danes need us the most — becoming an even stronger carrier of parcels and e-com partner, a service which is increasingly in demand,” Andreas Brethvad, PostNord Denmark's communications director, told The Parliament. “Adapting to the times and embracing technological advancements is mandatory for any business.”

Competitor DAO has taken up delivering post to the blind. Autonomous territories like Greenland have separate providers. For now, PostNord will still need to handle specific services, such as international post and covering the country's 70 inhabited islands.

At some point, these responsibilities may also be up for grabs. It's not clear what happens if no one takes them.

In post we trust

Without letters to drop in them, Denmark's some 1,500 iconic red postboxes will start to vanish across the country as soon as this summer. If drop-off points become more concentrated in town and city centres, it may be more difficult for elderly and disabled people to reach them.

“It's a really, really important service for these people,” Cordes said, calling physical mail a “lifeline.”

A symbol of public service, the disappearance of postboxes comes at a time of widespread public doubt about governments’ ability to provide for their societies. A 2024 OECD survey found that 44% of people across OECD countries had low or no trust in their national government. Denmark fell below that average, at less than 42%. The country saw nearly a five-point drop in moderate-to-high trust between 2021 and 2023.

Even small features of everyday life, such as a postbox or interaction with a postal employee, can boost the bond between citizen and society.

“It's about how can that community engagement piece be built in so that the outcomes are fair and inclusive?” Nick Thompson, the CEO of the Centre for Public Impact, a global non-profit, told The Parliament.

Some public services are trying to answer that call. France's La Poste, which has seen costs spike with inflation and shrinking mail volume, launched a programme in 2017 to check in on older people. About half of the company's 73,000 postal workers received training to participate.

What used to be strictly mail routes are now weekly visits to subscribers. Postal workers bring a community newsletter with them as a means of keeping people informed and engaged in life around them.

“We are seeing trust in government institutions and government services falling,” Thompson said. “Governments need to rethink how that trust and legitimacy is built in a digital age.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.