Despite a slew of negative headlines, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party is still on track to pick up new seats in the European Parliament when Germans go to the polls on Sunday, experts say.

The AfD’s lead candidate for the EP elections, Maximilian Krah, was forced to suspend his campaign and step down from the party’s board late last month after he said in an interview with the Financial Times that not all members of the Nazi’s SS paramilitary organisation were criminals. Krah’s comments were met with widespread criticism – including from one-time allies like France’s Marine Le Pen.

The Identity and Democracy (ID) group in which both Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) and the AfD sit in the EP expelled the German party the same week, complicating potential alliances after an election in which the far right is expected to make significant gains.

At the same time, an aide to Krah is currently under investigation for allegedly spying. Arrested in April in Dresden, Jian Guo is accused of sharing information about the European Parliament with a Chinese intelligence service.

But many German voters seem unperturbed by the upheaval in the AfD.

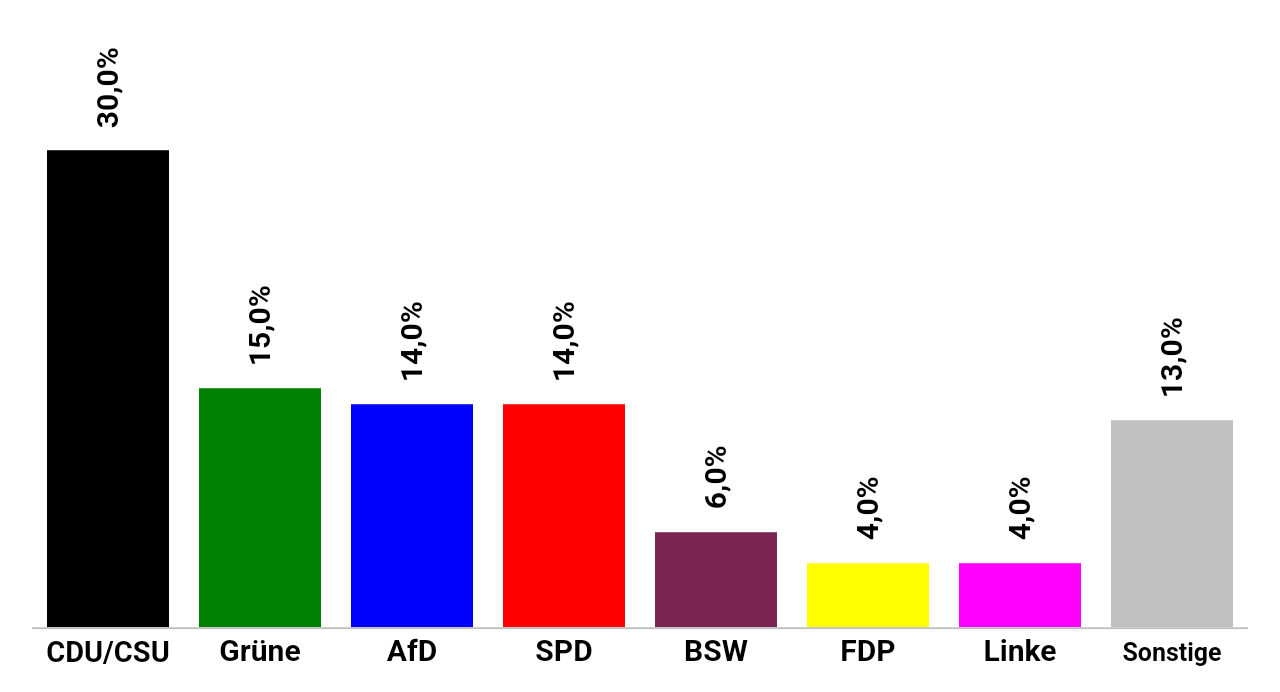

The party is expected to garner 14 per cent of the vote in the European elections, according to Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, making it the third most popular party in Germany – one percentage point behind the Greens and about 16 behind the leading centre-right Christian Democrats. That’s an improvement on the 2019 elections, when the AfD took home 11 per cent of the vote.

A May poll of German voters for the 2024 European elections. Source: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen/Dawum

A May poll of German voters for the 2024 European elections. Source: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen/Dawum

Still, the AfD lost some voters in January after investigative journalism group Collectiv reported that senior members of the party had met with neo-Nazis to hash out a plan for the “forced deportation of millions” of people living in Germany. Polling from Forschungsgruppe Wahlen from the start of the year had showed the AfD with an approval rating of around 22 per cent, but since then the party has polled steadily around 15 per cent.

The AfD may have lost some of its “soft voters” – those who supported the party as a protest against the mainstream, rather than over ideological considerations – but its core voting base remains intact, according to Nicolai von Ondarza, head of the Europe division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

AfD supporters remain loyal to the party in part because it has been outspoken on issues that resonate with them, particularly cracking down on migration, says Marcel Lewandowsky, a political scientist who works with Correctiv and the University of Mainz.

Ninety-one per cent of AfD supporters are concerned about an influx of migrants, according to a 2023 study from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. And nearly 100 per cent of Germans who back the AfD are dissatisfied with the country’s governing coalition of the centre-left Social Democrats, the Greens and the liberal Free Democratic Party, a survey by Statista from late last month showed.

In regional elections across Germany over the past year, the AfD has continued to demonstrate its growing appeal. In late May, in the right-wing east German state of Thuringia, the AfD captured more than 25 per cent of the vote, up from 17.7 per cent in 2019. The Christian Democratic Union eked out a win by less than two percentage points.

“And what you see in some parts of Thuringia is that the AfD is now competing with the conservatives [Christian Democrats] for votes, which means that the political left, the centre left, is pretty much diminished or even wiped out in some in some regions,” Lewandowsky says.

A new AfD-led group in the European Parliament?

On the European level, the conflict between the AfD and Le Pen has been looming for some time, von Ondarza says.

“It is clear is that RN and many other right-wing parties are trying to make themselves capable of governing and to give themselves a more moderate image to win votes. And the AfD has developed in exactly the opposite direction,” he explains.

After the elections, the AfD may be forced to form its own parliamentary group in the EP – a move that would require the buy-in of 23 MEPs from seven countries. One such political partner could be Kostadin Kostadinov, the leader of Bulgaria’s ultranationalist, pro-Russian Revival party, or Vazrazhdane.

“We will have the opportunity to create a real conservative and sovereigntist group in the European Parliament,” Kostadinov reportedly said of the AfD.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.