The exhibition Generations of Resilience, which opened last week at Brussels’ Hangar Photo Art Centre, brings together the artistic universes of 22 Ukrainian photographers spanning three generations. Fittingly spread out over three floors, one per generation, this haunting and poetic show traces recurring visual motifs – along with the ongoing struggle for freedom and search for identity – throughout the country’s photographic history. Since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of the country in February 2022, Ukraine has been at war, and life – and art – have changed in every way.

The Parliament’s Sarah Schug sat down with the creative mind behind the exhibition, Kyiv-based curator Kateryna Radchenko, to discuss the disappearance of the conceptual photography genre in the country, the challenges of organising an exhibition during wartime and art as a means of survival.

Curator Kateryna Radchenko

Curator Kateryna Radchenko

How do you ensure the war doesn’t overshadow the exhibition – or do you want to use it to draw (the at times diminishing) attention to the invasion? Is there a political dimension to it?

Life in Ukraine is all political. Just take my personal life experience: I was born at the end of the 80s, and lived through the Soviet period, gaining independence, the political and economic changes of the 90s, the first revolution in 1991, the second revolution in 2004, the revolution from 2013 to 2014. Now, there’s the war. All my life I’ve been affected by political changes.

It’s not possible to separate it from politics. You can see it through the exhibited works by photographers from three different generations. We didn’t have a plan to only select artists who incorporate a socio-political reflection in their work – it’s just unavoidable that these events influence the artists and change their practices.

What do the generations featured have in common?

Having to fight all the time – for your identity, for your country, for a better life. The Kharkiv School of Photography, which emerged in the 70s and 80s, was a revolutionary movement created to fight the Soviet system by exposing and criticising the reality of life at the time. It was a visual protest: photography was used to stand up against the system. Then, after Soviet rule ended in the 1990s and 2000s, the main questions were, “What is Ukraine?” and “What is a Ukrainian artist”?

It was a search for identity, something that shone through in the work of photographers who explored these questions through all kinds of aspects, from the body and culture to the social and the political.

Now, it’s again on another level. We’re already 10 years into the war and two years inside a full-scale war. This means that the young generation, 18 to 20-year-olds, have spent half their lives in wartime. It’s difficult to imagine how traumatised these kids are. This is also reflected in their photography, through which they try to deal with this traumatic experience and find a way to live with it.

That’s what connects all generations – this fight and using photography not only to archive moments but also to pass through their traumatic experiences and search for a way to move forward. There is also a connection through the visual language. The photographers from the Kharkiv School opened new horizons through their different experiments with collages and painting on photographs, methods that reappear in contemporary works.

Using photography to take distance from what’s happening and analysing it can also be a form of protest. Having the camera in between can give you a different perspective.

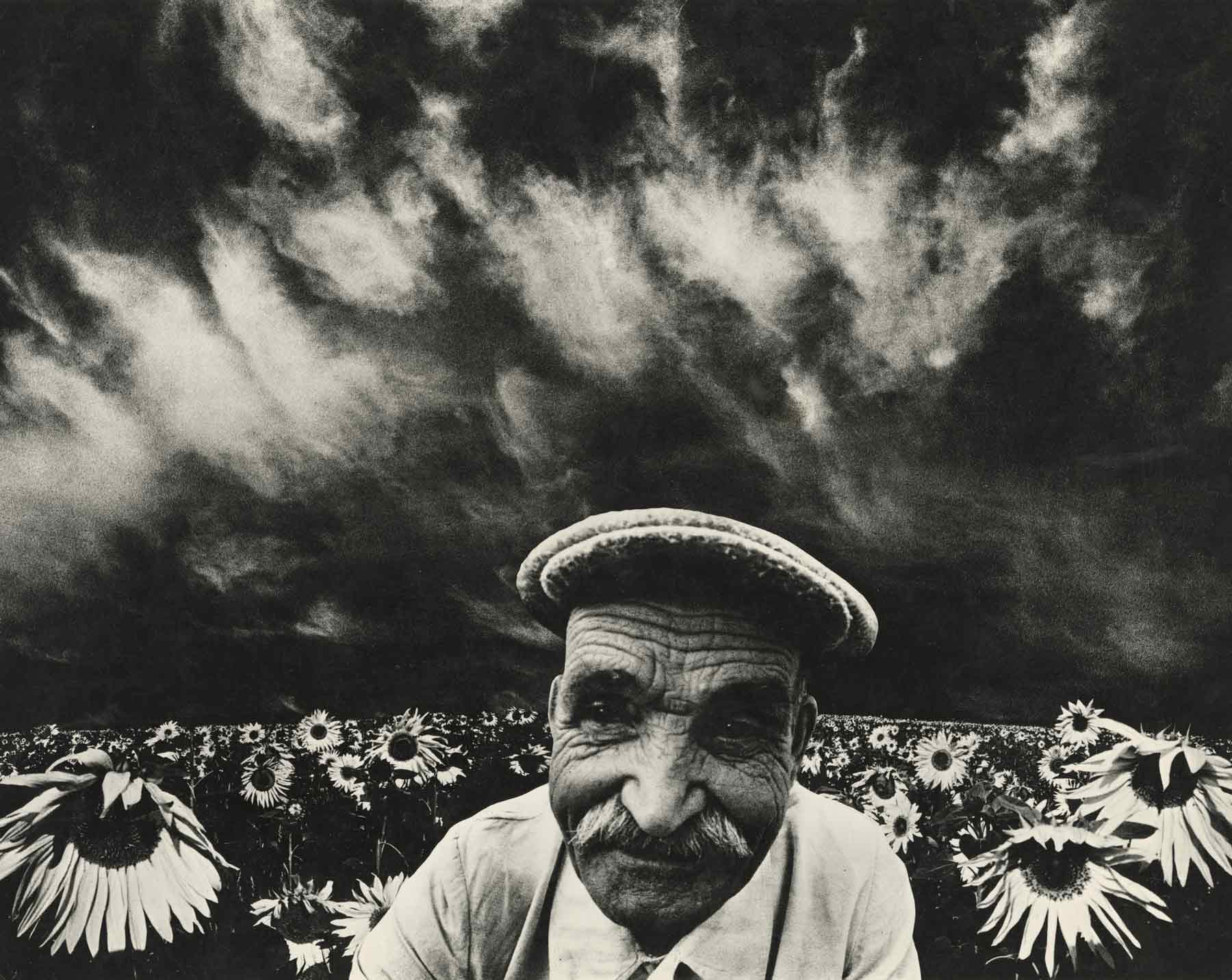

Sunflowers II by Oleksandr Suprun, a member of the Kharkiv school of photography

Sunflowers II by Oleksandr Suprun, a member of the Kharkiv school of photography

Does the war also foster a movement in the opposite direction – escapist art, so to speak?

Most projects by young photographers are connected to the war. It’s not possible to think about something different when living in Ukraine. You can’t think about self-discovery when it’s not relevant to the war. You can’t think about ecology when it’s not relevant to the war. It’s not possible. Even artists who don’t live in Ukraine. Everyone has relatives and friends there, and everyone knows someone on the frontline. It’s always present.

What were the logistical challenges in organising the show considering the current situation in Ukraine?

The original works came from the Kharkiv Museum of Photography. When the escalation started, its staff managed to bring the collection to [the European Union], and the collection is now based in Germany. As to the new generation, all works were sent digitally and printed here.

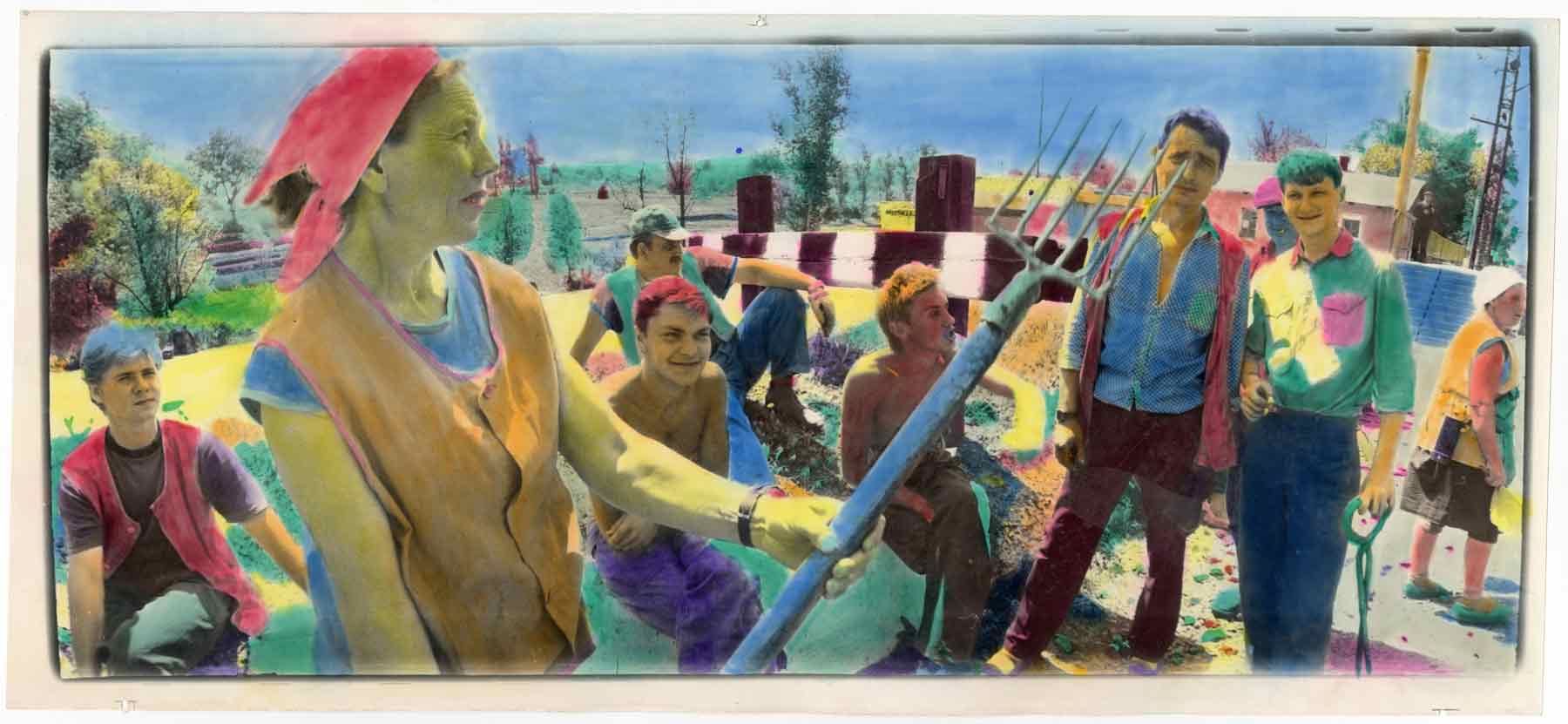

Viktor Kochetov is a representative of the Kharkiv school of photography

Viktor Kochetov is a representative of the Kharkiv school of photography

What’s the photography and artistic scene in Ukraine like right now? Are events still being organised?

Everything depends on the district you live in. Closer to the frontline it’s dangerous: there is no art, not even access to food sometimes. It’s dangerous and bombs fall daily. It’s all about hiding and surviving. Big cities like Odessa or Kharkiv are in risky territory – they’re on Russia’s radar. You have a lot of rockets but still, life is going on. Public events are happening, including art. It’s a question of how to work with this new reality. When you go to the theatre and hear a siren, everything will be stopped and you go to the shelter. In the western part [of the country], there are fewer attacks and more events, adapting to the new conditions and safety rules.

Art is back because you still have to live and move forward. Art helps with that. It helps to catch a break, to process things, and share experiences.

What does this mean for the photography festival you have been organising in Odessa?

Unfortunately, we are not able to do it in the same format as in the past when it included a lot of different exhibitions and gatherings. There are no shelters in Odessa, and we as organisers don’t want to carry the responsibility for other people’s lives. When you gather people, you have to provide shelter and when there’s no shelter, it’s better not to gather. That’s why our team has changed the format. Instead of the festival, we offer different support programs for Ukrainian photographers: mentorship for teenagers, a support program for photographers on the frontline, lectures… We are doing a lot but in a different way.

From the series Invasion by Maxim Dondyuk

From the series Invasion by Maxim Dondyuk

Has there been a shift in Ukrainian photography caused by the current war?

The war changed photography styles. In the exhibition, we show photography series by the same artists from before and after the escalation, and you can see radical changes. One artist for example, who used to paint on his photographs, using colour and humour, now shoots black and white images from the frontline. Humour is an element often present in Ukrainian art; it helps you to survive. Another [photographer] used to do street photography with a dash of irony; now he is making portraits of wives and kids who lost their men and fathers in the war. A lot of photographers switched and became war photographers.

It’s not possible to think about something else [other] than the war. Life in Ukraine has changed at such a rapid pace; each day you have to adapt to something new. First it was rockets, then ballistics, then drones, then a winter without electricity and light. Each time, there’s something new. All this adaptation to things you never had to deal with before takes so much energy. Artists in Ukraine mostly try to document these daily changes because, in order to be able to do conceptual work, you need time and a safe space to reflect. We don’t have that.

Target by Sasha Kurmaz

Target by Sasha Kurmaz

What do you hope visitors take away from the exhibition?

I hope it shines a light not just on Ukrainian photography but also on Ukrainian history. That it becomes clear that our fight has not just been going on for the last two years, but much longer – that we have been fighting generation after generation after generation. [I hope] that it becomes clear that we decided in which direction we want to move, and that we are dying for it. This is our decision, about our identity, who we are.

With this recent escalation, Ukraine was put on the global map, but people didn’t know much about it. I hope this exhibition clarifies the historical, political and social connections, and helps people understand what is happening today.

You live in Kyiv. Was it always clear that you wanted to stay?

I didn’t want to leave, even though it’s dangerous. It’s a question of fighting and luck. You can be killed at any time. But I don’t want to leave my family.

Ukraine is going through radical historical changes, and for me, it’s important to be part of it. I think it gives me the chance and the right to do this exhibition, to share what’s happening, from an artistic but also from a personal perspective. If I lived abroad, it wouldn’t be fair. Like this, I can observe how life has changed myself, and I don’t have to rely on the media which doesn’t always provide the right information.

Lisa Bukreyeva

Lisa Bukreyeva

How did you come up with the idea for the exhibition?

Hangar invited me to do a show, and we started talking about it a year ago. But everything in Ukraine changes so fast, and we revisited the idea six months ago. For me, it was also important to understand the situation in Belgium and how to speak to the Belgian audience. I learned that the Kharkiv School had never been shown here before which is why I wanted to start with this historical aspect.

Additionally, I wanted to make sure to not just show works dealing with the war. There is a lot of that in the media and other shows already. I wanted to go a bit deeper and not just stay on the surface. I hope I managed to show another perspective, the historical connections – something that can be relevant for other countries as well.

Generations of Resilience runs until 23 March.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.