Antoine Angé made a name for himself in France after infiltrating the 2017 election campaigns of several local political parties and publishing cartoons about his observations on social media under the alias Kokopello.

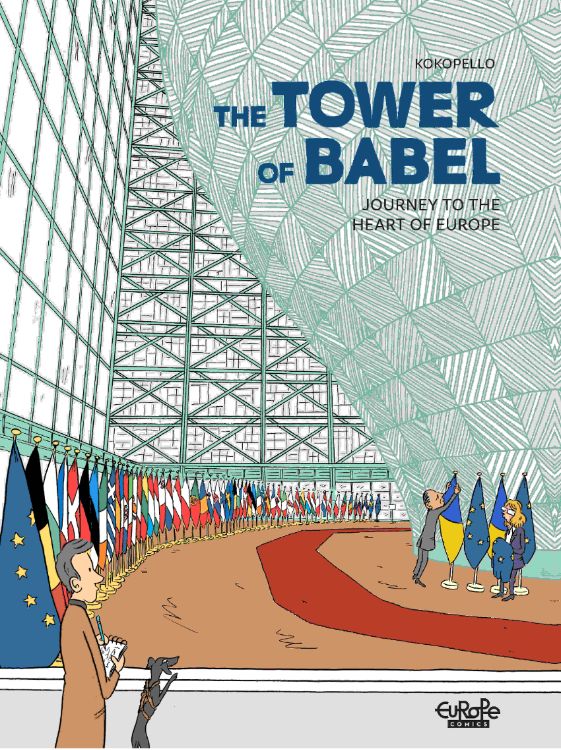

Today, the 32-year-old Frenchman is an established political cartoonist, and in May he released a graphic novel centred on the inner workings of the European Union, just in time for the European elections in early June. Pen and notebook in hand, Angé immersed himself in the Brussels bubble for 18 months for The Tower of Babel: Journey to the Heart of Europe, which manages to be both educational and playful.

With a keen eye and a touch of humour, Angé allows readers to get up close with MEPs, commissioners, ministers and journalists. He lifts the curtain on the EU institutions, and takes us to Brussels – along with many other locales including San Francisco and cities in Albania and Ukraine – while tackling policy themes such as climate change and immigration.

You studied cinema. How did you get interested in politics?

My interest was sparked in 2016, when Donald Trump won the elections in the United States and Brexit happened in Europe. I’m part of a generation [for whom] social networks play a big role, and I saw them have a lot of influence in the process – think Cambridge Analytica. I felt there was a filter between the social networks and citizens, and a growing gap with the political world. I didn’t want to be fooled. That’s when I decided to infiltrate the French political parties and see it all from the inside.

For The Tower of Babel, you needed officials’ permission to access the EU’s buildings. Did this make things easier or harder?

You can’t just get into the EU institutions as an average citizen. Even I had difficulties obtaining access at times because I’m not a journalist with a press card. At the [European] Council, for example, I was lucky to eventually come across an Italian whose children love graphic novels and who got me in. Being hidden and anonymous is interesting because people pay less attention to what they say. If you give them a microphone, they will be much more stoic. I was still quite free as they weren’t wary of a graphic novel author. We’re often just perceived as these little cartoonists making pleasant stuff, like Asterix or Tintin. Politicians don’t necessarily pay attention to us and tend to forget that there’s a text accompanying our drawings.

You made it into the limousines of commissioners and gained access to the Council negotiations. How did you manage that?

The French foreign ministry helped quite a lot as they knew my previous work and tone, which is not mean-spirited and just offers another way of looking at politics. They told me: “Europe is so unknown to citizens; we're going to help you see as much as possible.” It also helped that political comics are growing enormously in France. It’s part of the culture to open the door to cartoonists. There is even a special badge for [us] in the National Assembly. The biggest difficulty for me was that in other countries this is not the case. Some refused because I didn’t have a press card and they didn’t understand what I wanted. But commissioners – [Thierry] Breton and [Frans] Timmermans, for example – were sensitive to this approach and accepted quickly.

In your novel you cover much more than just the Brussels bubble. Was this planned?

For my first graphic novel about the National Assembly, I went back and forth between Paris and the French regions. I found it interesting to show both perspectives and to connect them to [real world] examples. I also spoke to a German journalist who had been covering the European Union for 17 years. He told me that if I really wanted to understand the EU, I’d have to speak to more nationalities and go into the capitals as well, where the EU will show a different face. The EU does remain a bubble where insiders who know how it all functions communicate with each other. I also wanted to get out of the bubble and include citizen voices.

In May, Antoine Angé released a graphic novel centred on the inner workings of the European Union.

In May, Antoine Angé released a graphic novel centred on the inner workings of the European Union.

In the beginning of the book, you mention the anti-EU views you encountered in France. Where do you think this Euroscepticism comes from?

I was born in 1991, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. I did not know a Europe divided in two. And I did not see the great achievements of the EU. When you delve into its history – the European idea of peace – you realise it’s something completely amazing. At the same time, people don’t see the concrete achievements of the EU. When there is something positive, governments claim it for themselves; and when something negative happens, it’s Brussels’ fault. But if we started looking at the functioning of this European Union more closely, we would realise that it’s the member states calling the shots. We haven’t explained the EU enough to people. The narrative is that it's a cold and complex machine which you won’t understand anyway. I try to fight against that with this graphic novel.

What was your initial impression when you entered the bubble for the first time?

When I went to the National Assembly, I knew exactly where to go. I knew the faces and places from TV, the different rooms, where what takes place. In Brussels, it was a very different experience. I felt completely lost. I didn’t know the people or the buildings; I had never seen them on TV. There was no familiarity. I didn't know at all where to go, who to meet, who was important. There was a moment where I thought it’s just not for me – too technical, too complex. But in the end, it’s not that difficult.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.